P. Adams Sitney, pioneering film writer and official representative of what was then called New American Cinema, was first invited to Yugoslavia in the summer of 1967. While there, he set up an impromptu screening session in his hotel room in Pula that, in retrospect, was the initial direct contact between the U.S. and Yugoslav film avant-garde. This first kino-séance is invoked as the subject of this research project and serves as primary case study, focusing on Sitney’s return visit to Yugoslavia, at the end of the same year and into 1968, for an official, larger, organized tour across the major cities of the Socialist Republic. This tour was titled theThird International Exposition of New American Cinema, and for many in Yugoslavia it was a turning point in their cinephilic devotion. These historical events, both institutional and improvised, and their implications, are crucial in ascertaining the influence and relevance of classical U.S. film avant-garde for a new generation of moving image artists from the former Yugoslavia. They also chart early significant work in film organizing and curating, particularly in relation to the canon of film art and how it was formed and solidified.

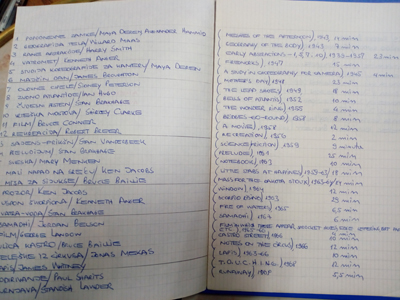

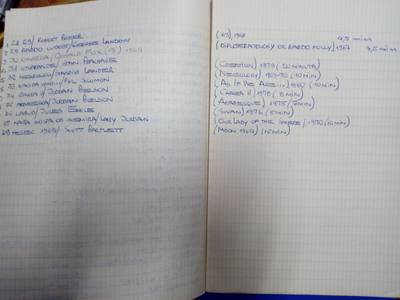

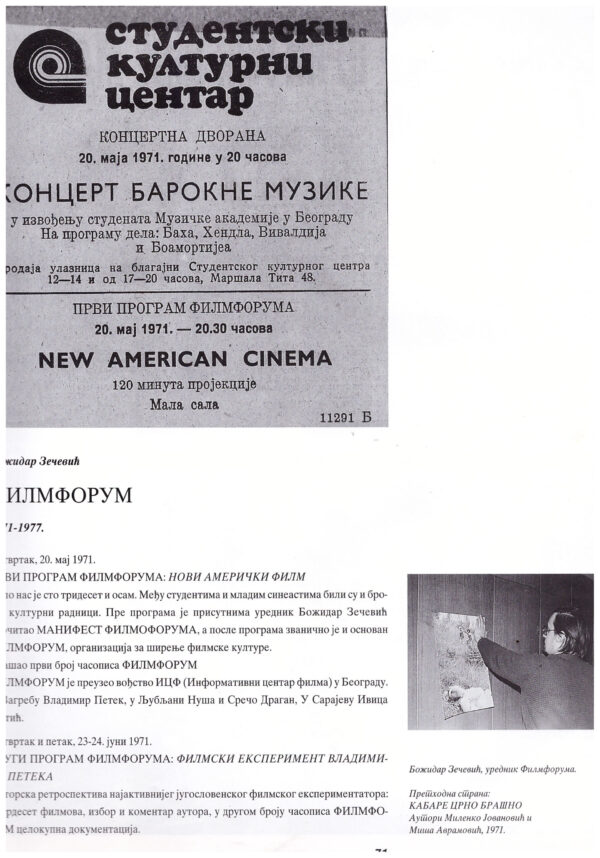

Phase 1 of this research project entailed gathering anecdotal evidence from those who were actually present at Sitney’s hotel room screening in Pula in 1967, at the time of the national film festival, and who can give eyewitness testimony to the legendary event. The subjects of this initial research were: P. Adams Sitney, the main protagonist, ambassador and chronicler for New American Cinema; Božidar Zečević, film critic and theorist who was at the time taking his first professional steps as a writer by covering the Pula Film Festival; and Dragomir Zupanc, student of film directing. Those interviewed who were not present at the initial Sitney screening, but who were key participants in this era, and who did see the subsequent Sitney screenings when he went on an official tour of the country, included: Slobodan Šijan, visual artist and film director who for a short time was film programmer at the Student Cultural Center (Šijan succeeded Božidar Zečević in the role); and Miroljub Stojanović, film critic and commissioning publications editor for Film Center Serbia. Key questions that were posed to the group of eyewitness included their recollections of Sitney, the films he showed, recollections of who was in the screening space with them, and general impressions of the U.S. avant-garde films presented, as well as any influences on their later work or the work of their peers. Key questions that were asked of the second group of participants in the era were about the institutions that showed these films for the first time, their recollections of which films were shown, and the impressions and influences that the films exerted on them and their colleagues. Unique questions posed to Sitney were his recollections of Yugoslavia, his recollections of technical details connected to his screening programs, and his reminiscences of the people he met and the audiences that watched the films, as well as their reactions.

The general sentiment among Yugoslav cineastes was that U.S. avant-garde films were a revelation. They altered the scope of possibilities for young Yugoslav artists in terms of representation, formal strategies, and ideological considerations. The films were also unique windows into a world that had never been seen before. Through Sitney and his anecdotes a picture was painted of this cultural contact from the reverse angle, including valuable memories of the sights and sounds of the golden age of Socialist Yugoslavia, memories of Yugoslav films that he had seen, including all the important figures that he interacted with. These oral histories have never been systematically documented before, and together they build up a portrait of the actual interaction between and influence of the U.S. film avant-garde on Yugoslav film artists. Anecdotal evidence such as this is a rich source of information and incredibly important to gather while the primary participants are still with us, in many cases still working.

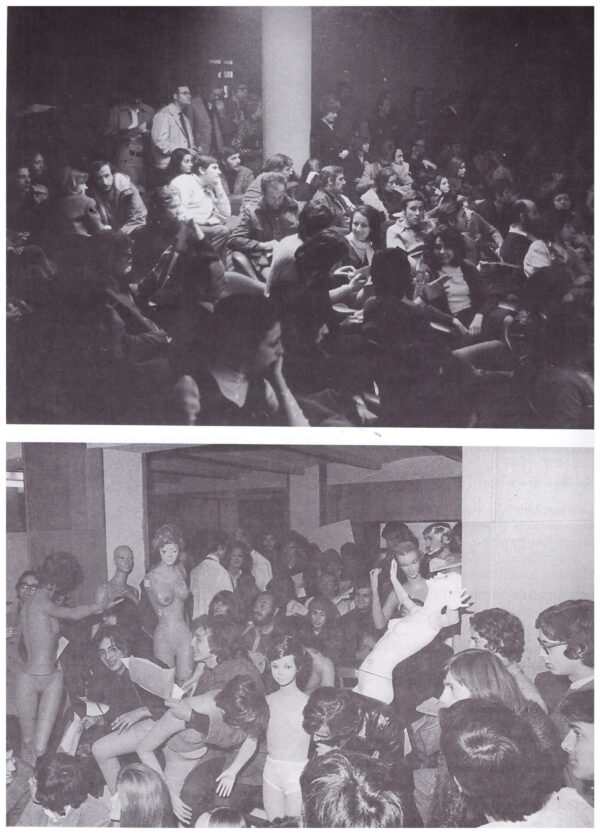

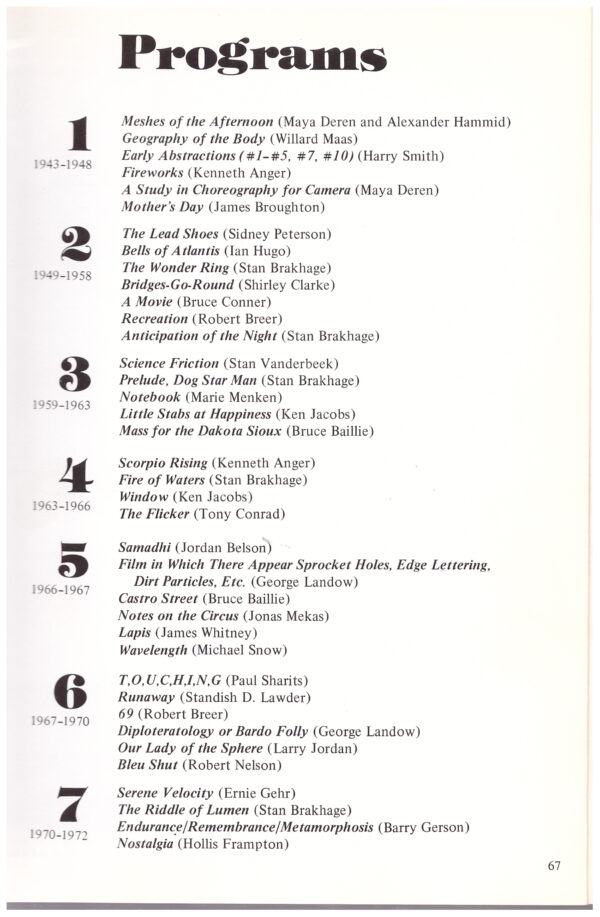

It would be hard to overstate the influence of the U.S. film avant-garde on Yugoslav filmmakers who in normal circumstances did not have access to other contemporary avant-garde movements. This influence and impression was often described as “a breath of fresh air,” “a true vision,” “a shock,” even “radical.” It was part of a general fascination with U.S. culture that also implied a strong dedication to jazz, among other objects of desire admired from a distance. Though there are key markers attesting to the residue of this influence in particular Yugoslav films, and those markers are easy enough to spot if one knows what to look for, perhaps the more illuminating research question is why certain films were chosen to be screened in Sitney’s programs, who did the selection, and what important works of film art of the time were not offered a similar platform. U.S. avant-garde films were widely influential the world over and Yugoslavia was no exception. Evidence of this first contact has often remained on a speculative or theoretical level. With this research project and with the protagonists of this story who are still alive and provide anecdotal evidence, the opportunity arises to sketch with greater accuracy what the actual shape and content of this exchange was. It also creates an opportunity to speculate on the alternative trajectories and histories that would have been written had a different canon of New American Cinema been offered to Yugoslav audiences and other audiences throughout the world.

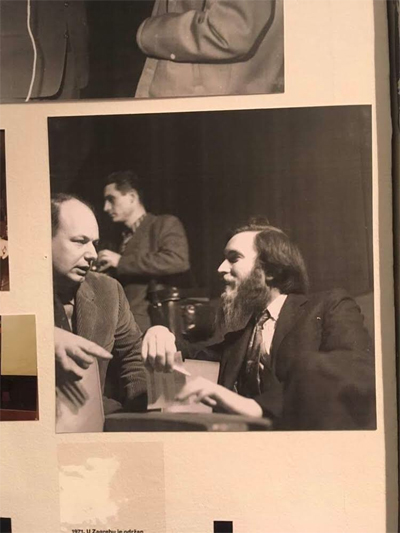

Sitney and the Third Film International are wonderful examples of the wider cultural exchange and influences between Yugoslavia and the U.S. Among other things, it is interesting to see that this exchange was initiated by informal means, relaxed encounters and personal invitations. This speaks to the openness of Yugoslavia and the ease with which cultural operators were able to initiate and realize projects. As the key representative and ambassador of film art from Yugoslavia, Dušan Makavejev, who first met Sitney and invited him to visit Yugoslavia, exerted an influence on many who saw his films and who recognized their fresh alternative spirit and impulse. Sitney traveled to Europe with films in his briefcase and, as can be seen from this research, was flexible and eager enough to organize impromptu screenings in his hotel room, literally inviting his Yugoslav counterparts to his living quarters, to share space and the art of cinema, which is an incredibly intimate form of séance. Zečević mentioned that discussions on the Hotel Rivera balcony about the films lasted well into the night, but this is more anecdotal evidence that we unfortunately do not have adequate memories to recount. As Sitney traveled through Yugoslavia he had many informal meetings, dinners and discussions with key representatives of the Yugoslav film avant-garde. Maybe nothing was decided from these discussions, maybe no future plans or projects were sketched out, but somehow the true form and essence of cultural exchange was expressed in these informal dialogues. There is no qualitative difference between cinephiles in one country and another. All are international citizens who speak a common visual language that transcends any barriers, and whose mysteries are revealed when lights are dimmed and windows are covered, and when the projector illuminates all.

Key Figures:

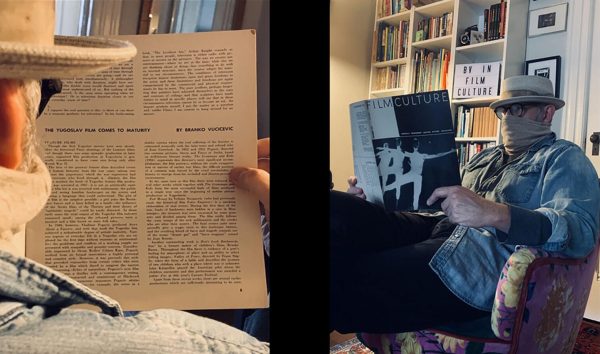

Adams Sitney was the international ambassador for New American Cinema in the 1960s. He wrote the book Visionary Film, which is the canonical study of US avant-garde film. Sitney worked at the Filmmakers Cinematheque and Anthology Film Archives in New York. He is professor of film studies.

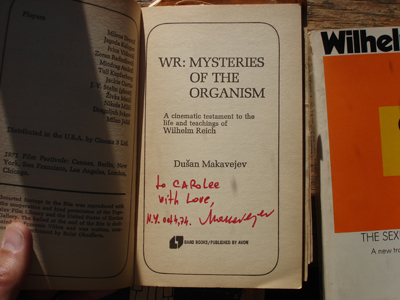

Dušan Makavejev was a film director and writer. He is of the most important European cineastes of his generation. Makavejev was called an “ambassador by Zečević,” who also stated his “belonging spiritually to the US avant-garde.” Makavejev first met Sitney and invited him to Yugoslavia in 1967.

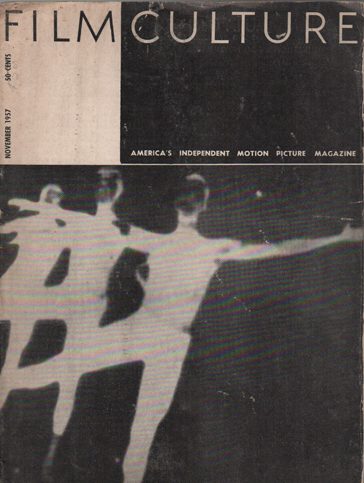

Branko Vučićević was a translator, critic, screenwriter and artist. He worked closely with Makavejev in the 1960s and also travelled with him. Vučićević translated and edited some of Sitney’s writings for the GEFF Bulletin, and wrote as a correspondent for the magazine Film Culture. He was an affiliate member of the Fluxus group and connected a lot of artists and nations during his career.

Božidar Zečević is a film critic, theorist and programmer. He worked at the Yugoslav Film Archive and was also the initiator and organizer of the program Filmforum at SKC.

Slobodan Šijan is a visual artist and filmmaker. For a short time he was organizer of SKC’s Filmforum. He witnessed the appearance of the US avant-garde in Yugoslavia in the 1960s and 1970s, then lived and worked in Los Angeles in the 1980s where he saw many other US avant-garde films.