Beginning with the exhibition titled “Savremena umetnost u SAD” (“Modern Art in the United States”), which was held in the summer of 1956 at the Art Pavilion in Kalemegdan, up until the end of the seventies, a multitude of significant exhibitions were held in Belgrade as offered by American institutions through the United States Information Agency (USIA). One could conclude that another such packet of “public diplomacy” had arrived with Robert Smithson’s retrospective exhibition, held at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade (then MSU, today MSUB) in the fall of 1983; however, this was not the case. Although the American government supported the exhibition, the idea for the exhibition came, above all else, from an initiative that was set into motion by two experts: Robert Hobbs, the curator of the exhibition and professor at Cornell University; and Professor Ješa Denegri, who, at that time, was the curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade. As such, unlike earlier projects and exhibitions the American side unilaterally offered, this exhibition arose based on the interest of both parties. For the history of art in Yugoslavia and Serbia, it is important to mention that Smithson’s retrospective was the one and only retrospective exhibition of any artist related to the New Art Practice movement that was in Belgrade in the 20th century.

Hobbs and Denegri met for the first time in the summer of 1982 in the Central Pavilion at the 40th Venice Biennale. Hobbs was already showing Smithson’s exhibition in the American Pavilion, while Denegri was the curator of the Yugoslavian Pavilion which were displaying the works of Boris Iljkovski, Andraš Šalamun and Edita Schubert. Over the course of a conversation, it turned out that the Smithson’s retrospective would be traveling throughout Europe during 1983, and that there was one empty time slot during which the exhibition would be available and could possibly be shown in Belgrade. Upon returning from Venice, Denegri, together with Ljiljana Simić, then MSU’s curator for international cooperation, went to a meeting with the cultural attaché at the American Embassy, where they presented the idea and the readiness of MSU for such an exhibition. However, in the words of Denegri, the idea was met with relatively cold reception. As it were, the American Embassy expressed its dismay in the fact that their previous project did not evoke the expected reaction from the public, and was even poorly reviewed a couple of times in the Yugoslavian press. These complaints were related to the large exhibition “Amerika sada” (“America Now”), which was organized in 1979 in a prefabricated dome, projected by Buckminster Fuller, which was set up in the park in front of the MSU.

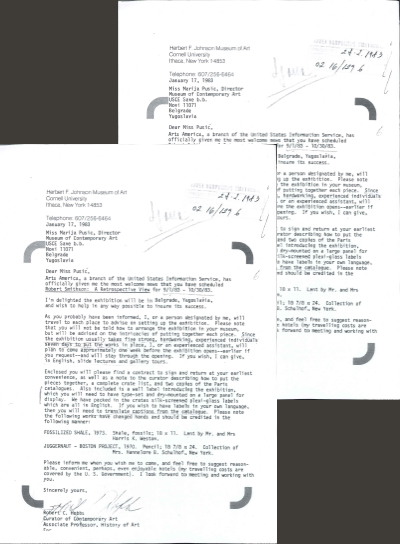

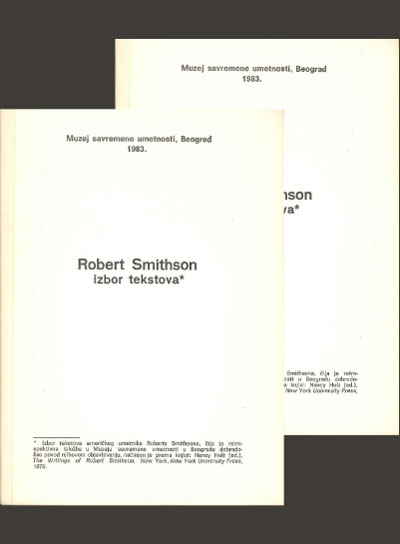

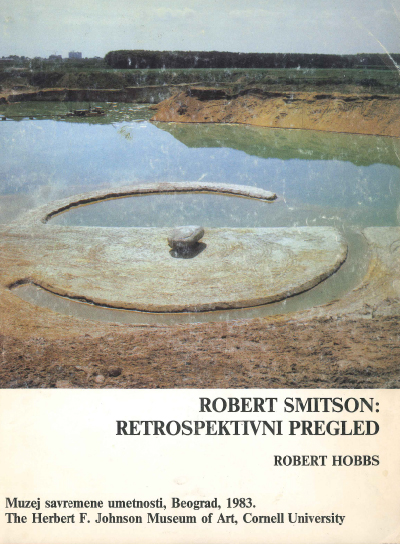

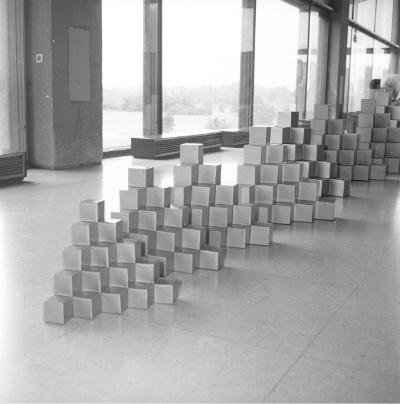

The 1979 exhibition would have been the last significant exhibition of American art in Belgrade had Denegri and Simić not been so persistent. And finally, in January of 1983, based on records that can be found in MSU’s archives, Hobbs informed Marija Pušić, the then director of the museum, that they had been notified by the USIS that the exhibition had been agreed upon and would be held between October 1-20, 1983. In the MSU archives, there is also a contract that was drafted between MSU and the Republic’s Cultural Association (Republička zajednica kulture), in which is evident that the Yugoslavian side covered all of the local costs of the exhibition, at the time amounting to 114,240.00 dinars. The exhibition was presented on the ground floor of the museum which was then used for traveling and temporary exhibitions, and a Serbo-Croatian version of the catalog was published titled “Robert Smitson: Retrospektivni pregled” (“Robert Smithson: A Retrospective View”). On the occasion, the museum also published a booklet with translations of Smithson’s seven essays, completing the serious institutional treatment of that the event received.

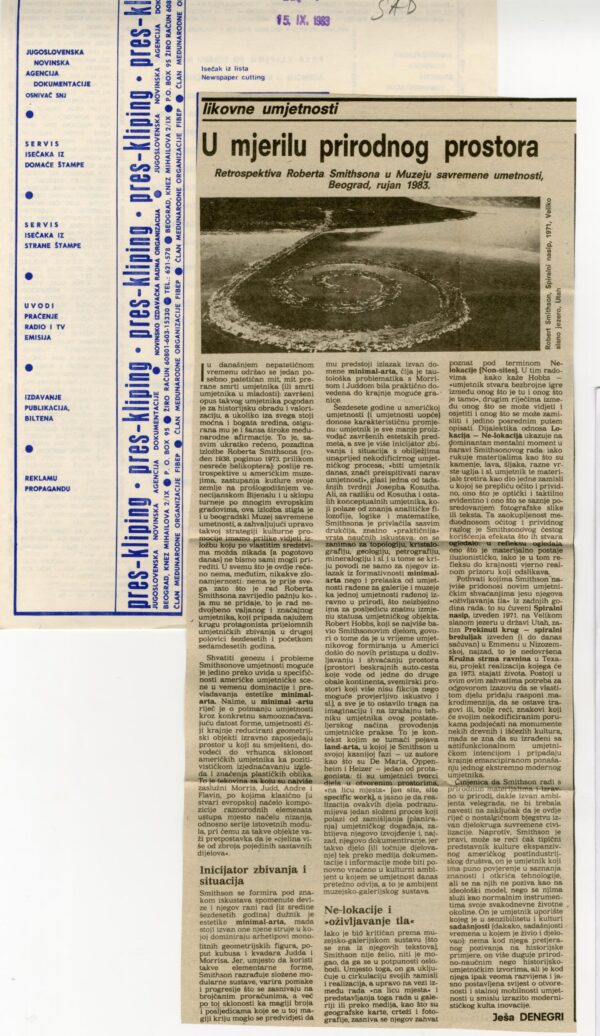

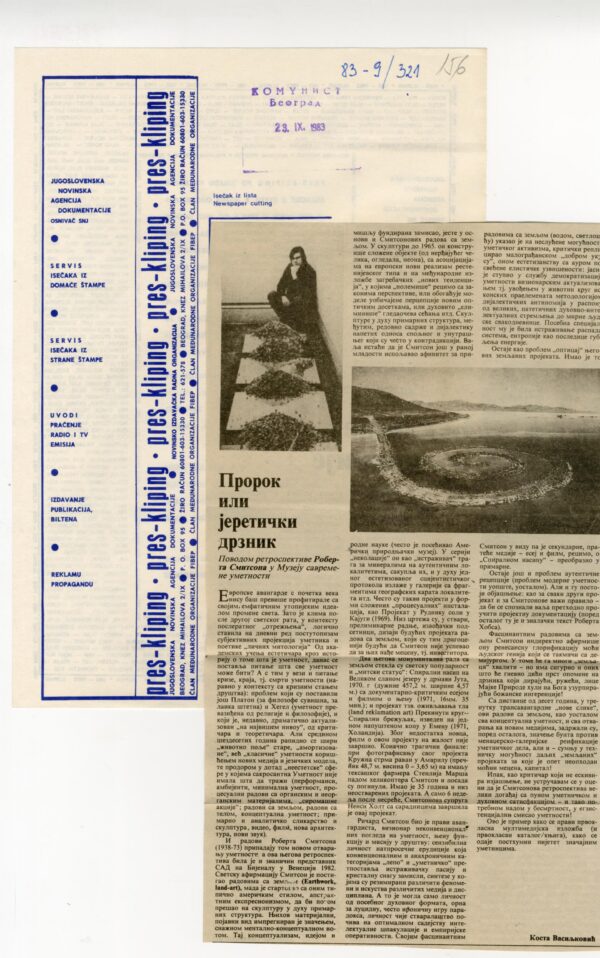

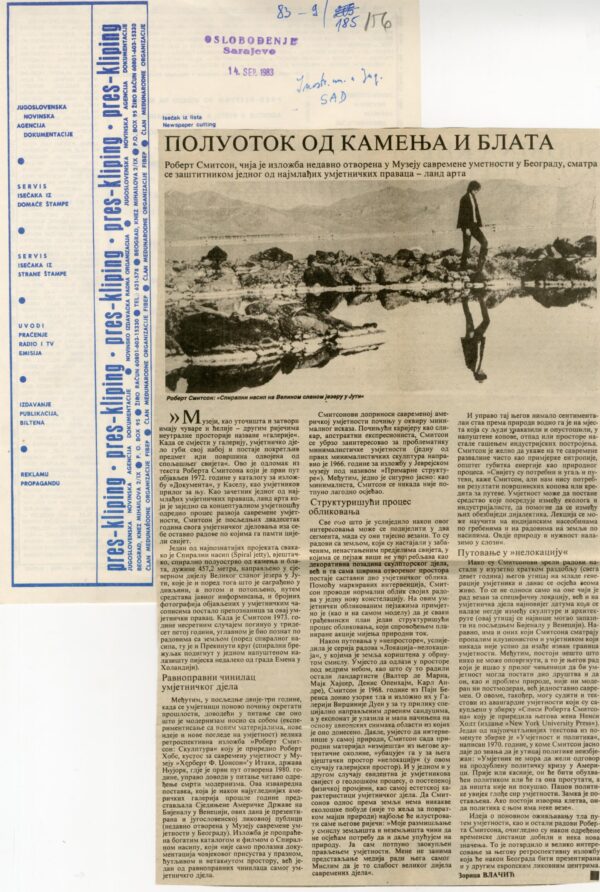

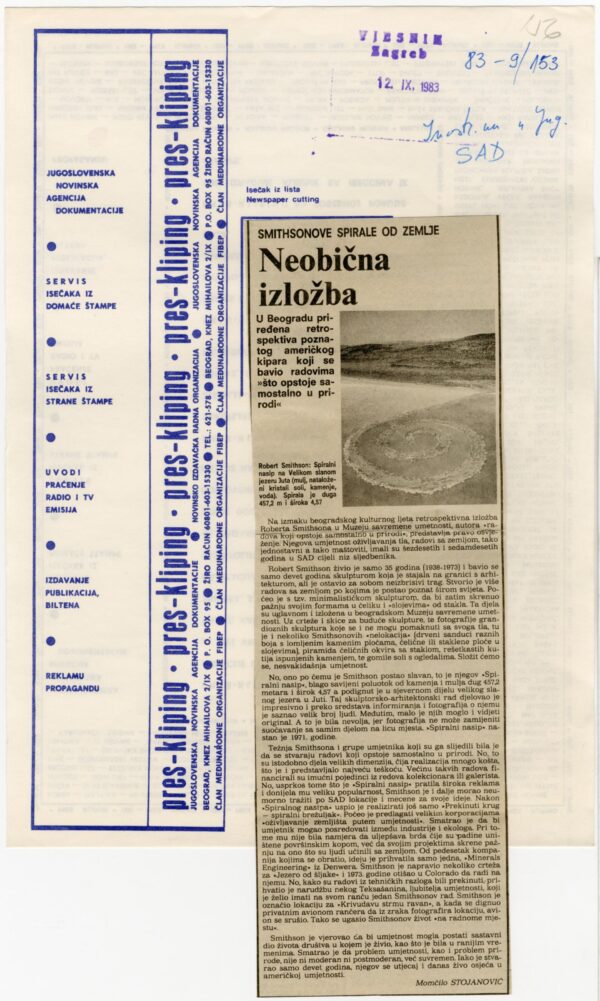

Additionally, and in contrast to some other foreign exhibitions in Belgrade that passed without much of a reaction, it turned out that the local art critics were both prepared for and competent to address an exhibition of this caliber. Denegri wrote three texts for various print media, and others wrote about the exhibition as well, including the very conservative Nikola Kusovac, who was not inclined to conceptual art in the slightest, who stated that Smithson was “One of the most important conceptual artists in the world.” Alongside a series of newspaper articles, Television Belgrade (TVB) also covered the exhibition with a five minute piece which can be found in their archives and will be available along with other archival material on this website. However, perhaps the most interesting text related to the exhibition a written in the first edition of the journal Moment, in which the artist Raša Todosijević will provide a unique analysis of the critical dichotomy of Smithson’s work—the relationship between site and non-site.

Smithson’s retrospective was also likely to have been the first retrospective exhibition of a conceptual or land-art artist in the world. The exhibition was in the fall of 1980 at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. One year later, Hobbs compiled the first monograph about the artist, who had tragically perished in a helicopter accident while filming his final “earth-work,” Amarillo Ramp, in Texas. Smithson’s death certainly resulted in him attaining cult status in the more recent history of art. However, it turned out that it was around the end of the 1990s that interest in Smithson’s work began to grow, as did his influence on modern artists. His influence became evident with interpretations becoming broader than any of the previous narrow views of his work as mere “land art.” From then on, a large number of works have appeared that pay homage to the artist, provide reflection, or remake of some of Smithson’s works and the general explorative-artistic process which he developed up until his premature death. What’s more, Smithson will become one of the artists whose work is considered characteristic for what will, from the early nineties until the present, be identified under the general concept of “contemporary art.”

Smithson’s work is considered exemplary in gaining understanding of the paradigm shift from “modern” to “contemporary” art. In newer theory, especially in Peter Osborne’s[1] texts and books Smithson’s work, particularly his use of the dialectic terms “site” and “non-site,” turns out to be one of the foundations for understanding that which can be termed the “historical ontology” of contemporary art, which Osborne determines to be a “post-conceptual” practice. The dichotomy of “site” and “non-site” is not only a question of the relationship between “gallery” and “non-gallery” spaces, but is also a question of the position of art itself, which is no longer determined by the aesthetic nor media paradigms that had been defined in the modern period. What’s more, the meaning of a work can no longer be located in the context of any clear demarcations in space, but rather, the work can be the relationship in which “site” and “non-site” are critically intertwined: through the presence of site and non-site, in the form of material samples from certain locations, photographic or film records, texts, drawings, maps, diagrams—or the opposite, as a means of constructing site through those very practices. Smithson gravitated towards a “logical picture” of art, by which he transcended the fundamental modernist dilemma between realism and expression, moving towards “an entirely ‘new sense of metaphor’ free of natural of realistic expressive content.”[2] What’s more, Smithson’s work, and above all his interest in the concept of entropy, could be interpreted today as having anticipated the biggest philosophical twist of the 21st century, so-called “anti-correlationism,” which assumes an ontological truth beyond our sensual relations which is beyond the finality of our cognition.[3] With Smithson as a historical reference, art today can gradually free itself from correlationism and cam become “a trans-material and post-disciplinary expansion of a thought experiment,” while the concept of “artistic expression” does more than merely freeing itself its technical or material specificities, therefore heading towards a break in the ideological connection between knowledge and disciplinarity.

The fact that the 1983 Belgrade art scene could meet with the work this artist cannot be disregarded. On the other hand, nor can one ignore the fact that Smithson’s work left what may be at first glance a small mark on the local scene, and how much, in those years, the scene was preoccupied with the trend of “new painting” and the postmodernist theory of art. However, with the beginning of the 1990s, the clear influence of Smithson’s presence in Belgrade can be made out in fragments which corresponded with renewed interest in the new artistic practices of the 1960s and 1970s, with the help of which postmodern relativism was transcended. From there, this investigation of the meaning and effects of Smithson’s retrospective in the second phase of the project “Ups and Downs, Highs and Lows… And the Forgotten” will be continued with particular artistic works, interventions, reflections and homages to Smithson’s work by local artists and others on whom Smithson’s exhibition and work have left an impact.

[1] See: Peter Osborne, Anywhere or Not at All – Philosophy of Contemporary Art, Verso, London, 2013.

[2] Robert Smithson, “A Provisional Theory of Non-Sites”, The Collected Writings, Edited by Jack Flam, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1996.

[3] See: Quentin Meillassoux, Poslije konačnosti, MAMA, Zagreb, 2016.

Key figures:

Robert Smithson, American Artist

Robert Hobbs, Professor at the Cornell University (Ithaca, New York) and curator of the retrospective exhibition of Robert Smithson.

Ješa Denegri, Curator for New Media at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade

Ljiljana Simić, Curator for International Collaboration at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade

Marija Pušić, Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade